left: Worried man, centre, Nippon Moon Landing, both silkscreen, running yardage; right appliquéd coat; front: collapsed tea table

left: Worried man, centre, Nippon Moon Landing, both silkscreen, running yardage; right appliquéd coat; front: collapsed tea table

Historical Note on the Broadside

First the news

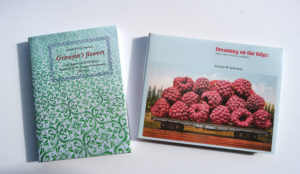

I have not posted in a while but that doesn’t mean the press is not busy. After the runaway success of my book Dreaming on the Edge, Oak Knoll Press hired me to copy-edit and design the new book on Robert Granjon’s ornaments by Hendrik Vervliet. I’ve known Dr Vervliet since the mid-70s and it was an honor to work with him, as well as a ton of fun to do the layout with his text and these wonderful 16th-century ornaments.

I have not posted in a while but that doesn’t mean the press is not busy. After the runaway success of my book Dreaming on the Edge, Oak Knoll Press hired me to copy-edit and design the new book on Robert Granjon’s ornaments by Hendrik Vervliet. I’ve known Dr Vervliet since the mid-70s and it was an honor to work with him, as well as a ton of fun to do the layout with his text and these wonderful 16th-century ornaments.

Frances has 6 works in the Hippie Modernism show at the new University Art Museum in Berkeley (housed in the old UC Press printing plant), on show for a couple of months. Not that she was a Hippie but she did work in textiles in the 60s. Shown is part of her work on display with running yardage, an engineered appliquéd coat, and one of her collapsed tea tables.

Frances has 6 works in the Hippie Modernism show at the new University Art Museum in Berkeley (housed in the old UC Press printing plant), on show for a couple of months. Not that she was a Hippie but she did work in textiles in the 60s. Shown is part of her work on display with running yardage, an engineered appliquéd coat, and one of her collapsed tea tables.

On Feb 8 Tom Raworth died.

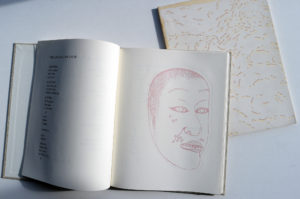

Tom Raworth by Barry Flanagan, 1973

Tom Raworth by Barry Flanagan, 1973

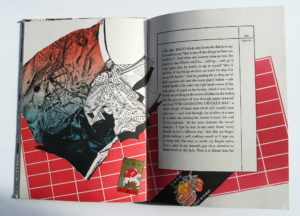

Tom was a unique poet and he also had an early career as a magazine publisher (Outburst) from his Matrix Press followed by his successful small press Goliard, which he ran with the visual artist and film maker Barry Hall. His early books were printed by one of my idols: Asa Benveniste at Trigram Press in London. I met Tom in 1973 when he was hanging out with the Zephyrus Image crowd — Ed Dorn, Holbrook Teter & Michael Myers — and embarrassed myself by immediately quoting his poetry to him. Frances and I asked him for something to publish and he gave us a spring-backed binder full of about 5 unpublished books. I wanted to publish his new poems, which came out as The Mask (Poltroon modern Poets volume 1) and Frances set to work illustrating The Logbook, which was part of a longer sequence called Cancer.

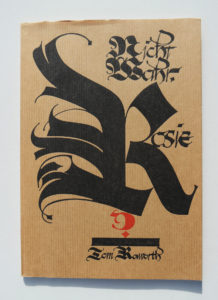

Her book was shown in the “Seventy for the Seventies” Show at the Grolier Club in New York. Since we had only produced 60 copies (in color by letterpress) we printed an offset edition in black and white. I asked Tom about a Fulcrum Press book called Nicht Wahr, Rosie? which had been printed but all copies destroyed in a flood in the publisher’s warehouse in 1970. Tom said we could have it, so we published it, with a cover by Arne Wolf.

Her book was shown in the “Seventy for the Seventies” Show at the Grolier Club in New York. Since we had only produced 60 copies (in color by letterpress) we printed an offset edition in black and white. I asked Tom about a Fulcrum Press book called Nicht Wahr, Rosie? which had been printed but all copies destroyed in a flood in the publisher’s warehouse in 1970. Tom said we could have it, so we published it, with a cover by Arne Wolf.

In 1979 it won the Award for Excellence in Typography from the esteemed American Institute of Graphic Arts. We were happy to get some recognition for the design but to us the poetry within is the incredible part of his work. We produced a fourth Raworth title in 1995: Muted Hawks. Tom read it on a flying visit to San Francisco and as he read I imagined driving (fast) through a city like Lima or Mexico City and glimpsing fragments of torn posters for wrestling matches or election campaigns. I asked him for the manuscript which he willingly gave me to create the work I had imagined.

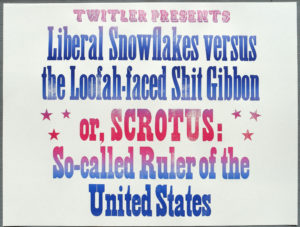

Also this month the biennial International Antiquarian Book fair came to Oakland. Among the mouth-watering displays of rare books a New York dealer had brought a dozen boxes of mid-nineteenth-century wood type. We have some nice wood type but have also missed out on some great collections that came along and then evaporated before our eyes. I suppose my new interest in display work came about by the election of “Agent Orange” as American President. I printed up TRUCK FUMP posters for the big Womens’ March in Oakland in January and handed them out, and also attended the demonstration against Milo Yannopoulous which turned nasty when the Anarchist black bloc showed up. So, needing a text to proof my new wood type, I created a spur-of-the-moment political poster.  This, like my other ephemeral work is available for sale on our ETSY site. (All proceeds from the anti-Trump posters will be donated to the ACLU.)

This, like my other ephemeral work is available for sale on our ETSY site. (All proceeds from the anti-Trump posters will be donated to the ACLU.)

And just to give this post some focus, here is an article I wrote in 1985 when Fine Print did a broadside round-up to show what North American presses were doing with their offcut paper. The only political broadsides included were by Glenn Goluska of Imprimerie Dromadaire in Toronto.

Historical Note on the Broadside

by Alastair Johnston (from Fine Print, vol 11, no 3, July 1985)

The broadside is a literary, artistic, and typographic form. Traditionally it is a bad example of all three, but for political or social history it is unrivaled by any shelf of scholarly tomes. It is hard to define, being something between a handbill and a poster. Its purpose is didactic or entertaining. I would exclude flyers that contain a sales pitch. It can be political, though then it sells ideology. The word follows “broadsheet” in the Oxford English Dictionary. A broadsheet is a large sheet of paper printed on one side only. Diderot said in 1878, “Pamphlets, broadsheets, sarcasms flew over Paris.” The definition of broadside comes after the nautical term meaning the whole side of a ship and from a second term which could also refer to the socially or politically corrective application of the printed form: “the simultaneous discharge of the artillery on one side of a ship of war.” The printed broadside, we learn, is almost synonymous with the broadsheet: “A sheet of paper printed on one side only, forming one large page.” Now that is puzzling, as a page is generally taken to mean part of a gathering of leaves forming a book.

Confessions, dying speeches, and ballads seem to swirl around the conception. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries broadsides filled the spot now occupied by the National Enquirer—indeed now occupied by most daily newspapers, for there are those of us who can’t distinguish the Murdoch and Gannet publications from the yellower (Hearst) forms. [N.B.: This was written in 1985 before the current cries of “fake news” overtook the media]

The early broadside is an active dialogue with the exigencies of daily life, its vitality undiminished by its seeming preoccupation with sudden death, rapine, and disaster. Its immediacy is caught in the German name, “fliegende Blätter,” or flying leaves.

On the somber end we find funeral orations and memorial verses, invariably darkened with heavy rules and coarse woodcut coffin borders, then dying confessions and warnings against crime, and a favorite category for pulpit fodder: meditations upon portentous events. We know that Voltaire’s optimism was shattered by the celebrated earthquake in Lisbon but those of a more complacent spiritual mentality could quickly trot out a “Poem on the Rebuke of God’s Hand in the Fire of Boston,” or “Warning Occasioned by the Eclipse” (reprinted in Ola E. Winslow’s American Broadside Verse, New Haven and London, 1930).

The broadside goes back to the earliest days of the press. By the sixteenth century, the practice of putting words of remorse into a condemned man’s mouth and then publishing them had already prompted this lament of the double execution:

At the gallows first, and after in a ballad

Sung to some villainous tune. There are ten-groat rhymers

About the town, grown fat on these occasions…

A particularly notorious murderer’s last dying speech might sell up to a million copies in London, so great was the demand for this literature. The broadside coexisted with the periodical and the almanac because it was more timely and could be more expansive. However, by the late eighteenth century it had lost ground to the daily newspaper. Nevertheless, in the early nineteenth century “Jemmy” Catnach restored it to prominence by successfully recapturing the naive crudity of a bygone era. The next seventy years, after the Napoleonic War, saw the doggerel flow unstanched from the Seven Dials district of London. Poor writing was characteristic of these cheap, populist ephemera. Sir Henry Mayhew, in London Labour and the London Poor (1862), records that there were then 700 individuals making their livelihood in Britain by singing and selling ballads.

Some of the comic balladeers—or “patterers”—worked in pairs: the straight man setting up the first couplet and his partner giving the witty payoff. In this respect they are not unlike the popular rappers of the present day, Sugarhill Gang and Run D.M.C. [ again, this was written in 1985], whose streetwise rhyming couplets in traditional anapests and dactyls evolved from the call and response of chain gangs and railroad crews in the rural Southern states and can be traced back beyond that to the Bakongo and Yoruba peoples of West Africa.

Like any popular phenomenon, the artificially quaint and nostalgic style of the Victorian ballads, coupled with the wretched poetry, wore itself out. “The decline so long bewailed by lovers of a picturesque survival dragged its slow length along,” says W. Henderson in Victorian Street Ballads (London, 1937). The ballad monger was replaced by the cheap songbook and the cheaper newspaper (not, however, until Catnach and his competitors had retired in comfort).

In the twentieth century, W. B. Yeats found the broadside a handy vehicle, and his sister’s Cuala Press issued a long-running monthly series from 1908. These featured hand-colored woodcuts by Jack Yeats, though traditionally the ballad printer would use any illustration or stock cut, unperturbed by the incongruity. Some poets, Helen Adam comes to mind, still excel at the form, and printers today are more likely to strive for a harmonious juxtaposition of text and image.

The richest collections of historic broadsides are those at the British Library (which includes a hoard of thousands amassed by the Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould) and the Pepys collection at Cambridge which houses an important historic group of 1,400 collected by John Selden, who wrote, “more solid things do not show the complexion of the times so well as ballads and libels.”

Alastair Johnston