Books breaking out of their bindings

Hedi Kyle & Ulla Warchol, The Art of the Fold, Laurence King, September 2018, reviewed by Alastair Johnston

In his novel The Diamond Noodle (Poltroon Press, 1980) Philip Whalen wrote:

A vision of the total BOOK — the thickness of an unabridged dictionary, a wrap-around cover such as a Chinese book has — something cross between a book, a portfolio and a file cabinet. Opened, it becomes immense. Each word has a bundle of papers in a pigeonhole or shelf, and along with the papers are samples of what the word is or what it means: small phials of earth, ore samples, patches of colored cloth, transparent envelopes containing coins, stamps (all these exempla bright, clear, colors.) With this equipment I can find out all I want to know about anything…

All things change slowly, but in the history of Artists Books there is a specific moment where the tide turned and structure and materials moved to the fore, a point at which Whalen’s fantasy started to become a possibility. The watershed came in the mid-1970s when Hedi Kyle taught at Oxbow and gave a series of seminars across the United States. From then on the arts of the book in America were transformed.

In the first quincentenary of printing in the West the codex format held sway. If a diagram needed to be animated, nifty inventions such as volvelles, could be inserted (with paper rivets) so that works of algebra and astronomy could have animated articulated diagrams. Woodcut-illustrated books were hand-colored to heighten their appearance; but for more sophisticated works, copper engraving (which was introduced shortly after letterpress) was used. The flat-printed gores of Gerard Mercator were cut out and glued to papier-maché spheres to create three-dimensional terrestrial and celestial globes in the 1540s.

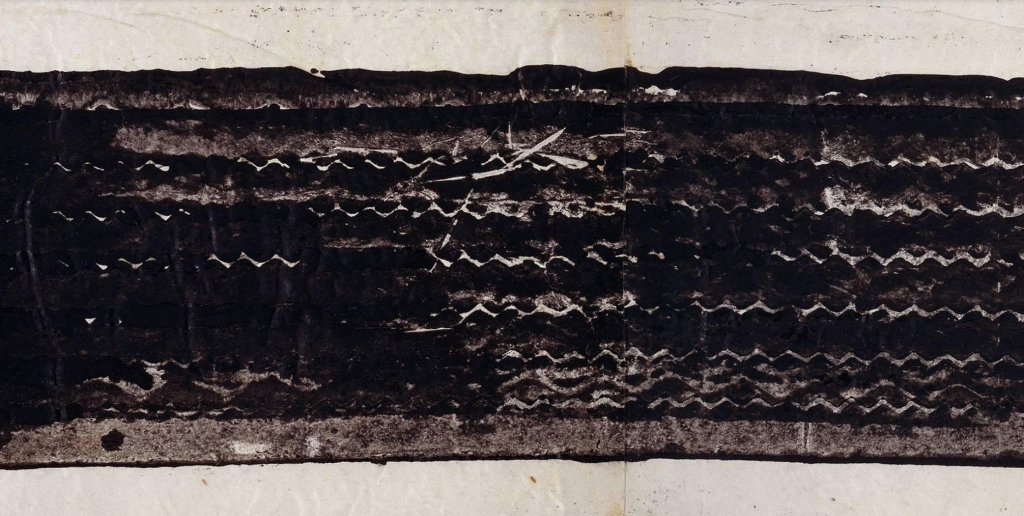

Fast-forward to modern times and you see artists engaging with the book form in interesting ways. Robert Rauschenberg took a unique approach to the scroll format with his “Automobile Tire Print” of 1953 when he asked John Cage to drive his car through black ink and across a long strip of paper, so John Cage was the printer and his Model A Ford the press. For those of us who love Japanese sumi-ink calligraphy but cannot read it, this transcendent work also speaks volumes about the texture and randomness (the fact that it was a rainy day) that can occur in something as simple and direct as ink deposited on paper.

A few years later we find Dieter Rot creating indecipherable works with his Daily Mirror Book of 1961 when he cut out random two-centimetre squares from the British tabloid and had them bound into a book (taking something common and quite worthless and giving it value in a new context), and his wicked Litteraturwurst where he ground up books with gelatin, lard and spices, and stuffed them into sausage skins.

Other artistic actions involving books were seen in A Humument (1966- ) by Tom Phillips, who painted out sections of pages revealing a new text, and Buzz Spector‘s carefully ripped apart books of the 1970s that also revealed paper landscapes of uncertain meaning. These enigmatic approaches reveal new texts while eradicating the original (which the artists themselves deemed worthless to begin with), but relate to the traditional book as El Lissitzky and Vasili Kamensky’s revolutionary works did.

In the world of small presses Zephyrus Image of Holbrook Teter & Michael Myers made flipbooks, comic books, origami birds and children’s games, especially those involving folding (cootie-catchers) and hidden pages, right at the start of the 1970s.

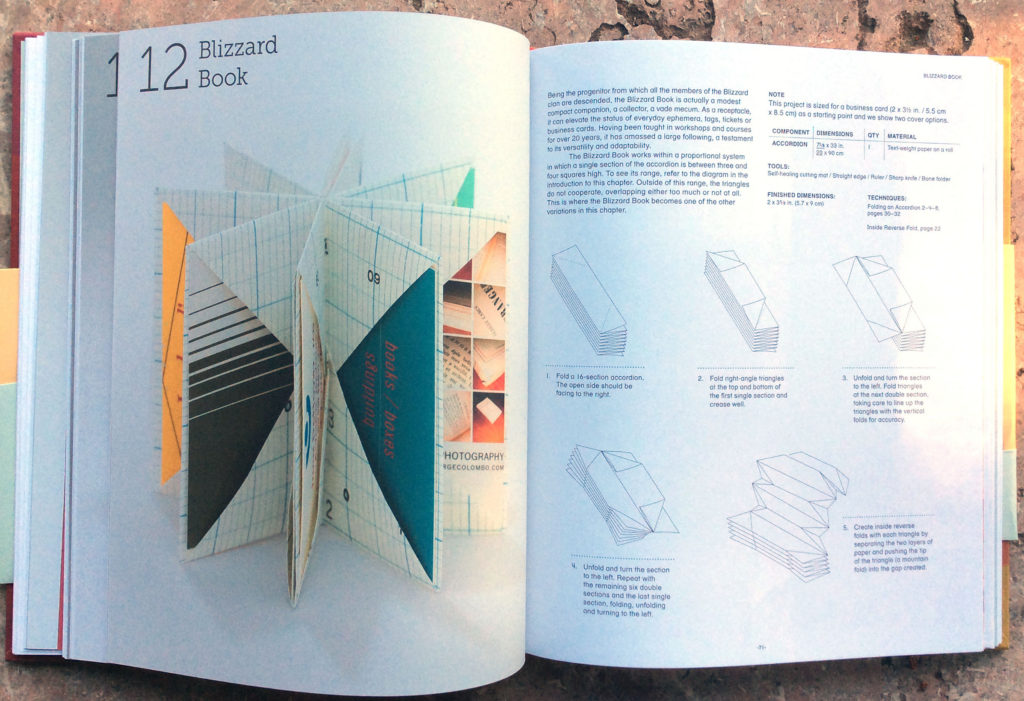

But the first true explorations of new approaches to structure were made by a conservator, Hedi Kyle, who began to think of the spine of the book as not necessarily a rigid component where the signatures were sewn together. Part of her conservation work involved deconstruction in order to repair old books and she began to find intriguing structural secrets under the covers of books. As part of her repair process, she became interested in non-adhesive bindings that could be taken apart again. She made models in order to understand the process. Being an artist herself, she would experiment with structures and invent variations on them. She began teaching bookbinding at the Center for Book Arts in New York and then book arts at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. In the mid-1970s her seminars, advertised by word of mouth, were sold out. In 1982 Wesley Tanner produced The Book of Benjamin by Michael McClure using her flag book format. The following year Susan King produced Women and cars using the same format. These were simple structures that moved from a fixed spine to an accordion spine that made the articulation of the book part of the experience of opening it. Unlike origami there is no fixed result. In terms of complexity Kyle’s project diagrams fall between a jigsaw puzzle and an IKEA cabinet.

It is not an understatement to say that the new discipline of “book arts” (which arrived when letterpress became “dead tech” in the 1970s and passed into the hands of artists) was given a boost with the arrival of Kyle’s structures. She was playfully expanding the notion of the book. Her diagrams were passed around and many small publishers and newly minted “book artists” started working with accordion spines and non-adhesive bindings. Her ideas were copied, misunderstood and misapplied, but above all sought after. Someone was even selling PDFs of Hedi’s diagrams on-line. Instead of sending a cease & desist letter, Hedi ordered one, downloaded it and then wrote the author explaining where it was wrong. In 2015, Dorothy Yule, a major Californian book artist, created a series of works in tribute to Kyle called Hediday: A Portable holiday.

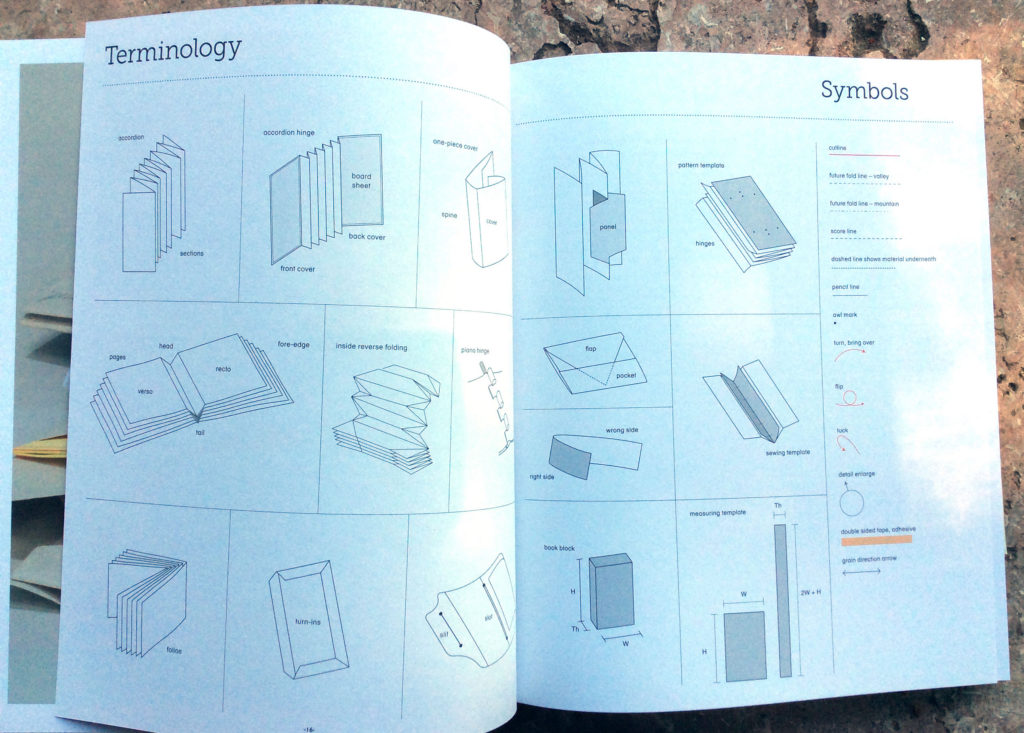

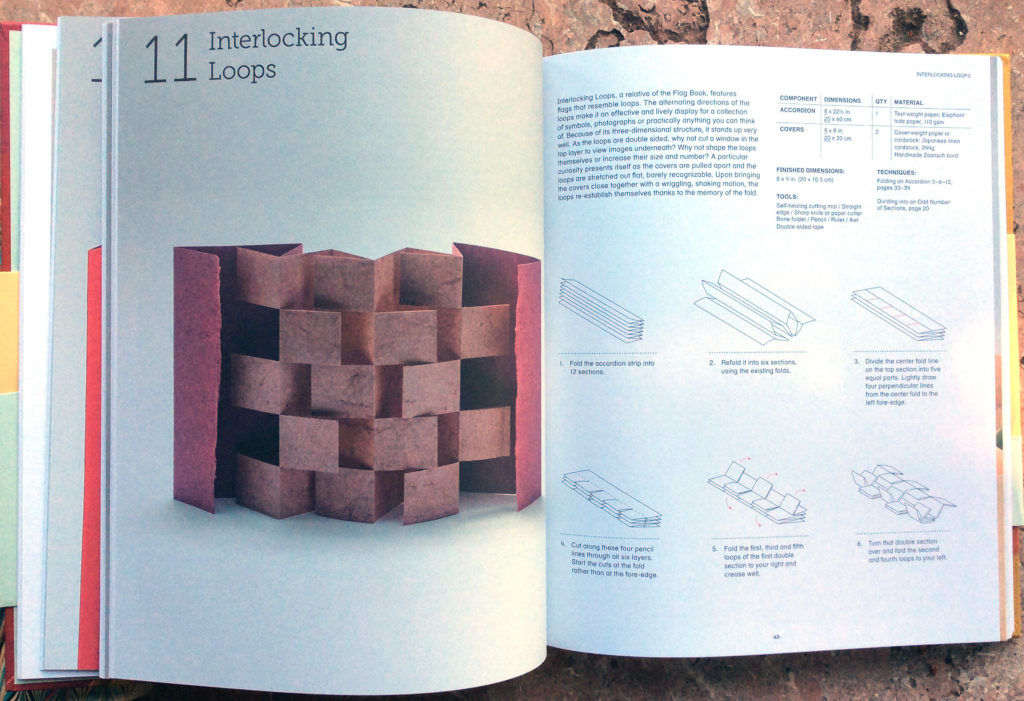

The publication of The Art of the Fold from Laurence King (192 pp., 500 illustrations, hardcover with obi — the publisher calls it a “belly band” but let’s not be vulgar) gives us the definitive Book Arts Cookbook. Here are 36 recipes, starting with how to fold an accordion (not as easy as you’d think, but in terms of a flexible sheet of paper, go to — with understanding comes wisdom) and ending with a wrapper to enclose your projects. Kyle’s diagrams are accompanied by clear photos showing the finished projects, from Accordions to Blizzard books, albums to enclosures. You’ll find a fishbone fold, star pop-ups, four-way map fold, the piano hinge, the Telescoping Ziggurat and the Spider book. I am tempted to add, But wait, if you buy now, you will also receive the Panorama Book and the Button pouch at no extra charge. Many of the projects are one-sheet books. The complex folding may seem a little daunting but it’s not Rubik’s-cube tough. If at first you don’t succeed, try again, as the spider said to Robert Bruce.

As her daughter, Ulla Warchol, grew up in the studio, Kyle says, “we spend many a day talking in folds.” Now Ulla (who graduated from the Cooper Union with a degree in architecture) has added architectural precision to the drawings. Kyle talks clearly about tools and materials, adhesives, and above all the joy hidden in the folds of the paper.