Our Stanhope Press

ANCIENT GREASE – Restoring a Stanhope Press

The Poltroon Press Stanhope

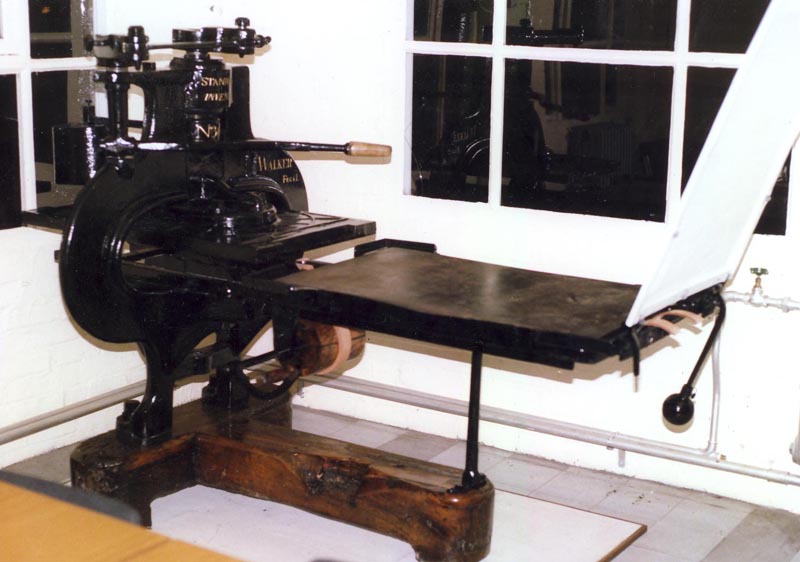

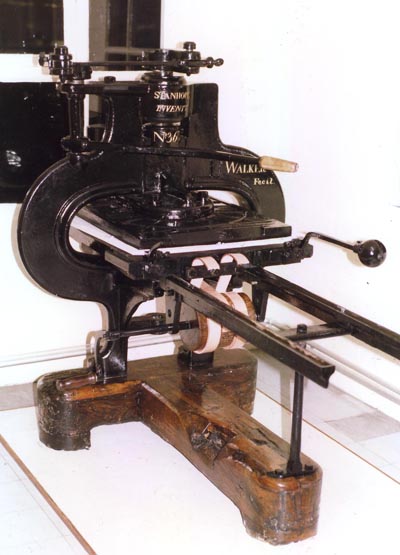

Stanhope presses are squat, chubby and fully functional, austere, industrial, modern-looking. And original. As the first iron press it revolutionized printing. Lord Stanhope himself was a revolutionary figure, devoting his life to science and technology and championing France in the face of English hatred. Though married to Prime Minister William Pitt’s sister, Hester, Stanhope opposed the war in the American colonies and urged parliamentary reform. He was in a minority of one in the House of Lords arguing against British intervention in French affairs during the revolution. On another occasion Lord Byron was the only peer who stood with him, giving and getting abuse from the other lords, who called Stanhope a “Jacobin.” Stanhope was so angry at the Lords he removed his family crest from his estate and retired from public life to work on philanthropic projects. The French dubbed him “Citizen Stanhope”! He put his fortune at the service of science; his all-iron press, built with the aid of a brilliant London engineer named Robert Walker, was the first result. He refused to copyright the design so anyone could build one. He invented a new microscope, and purchased the secret of stereotyping and made it public for the advancement of printing. In short, he was a great benefactor of mankind.

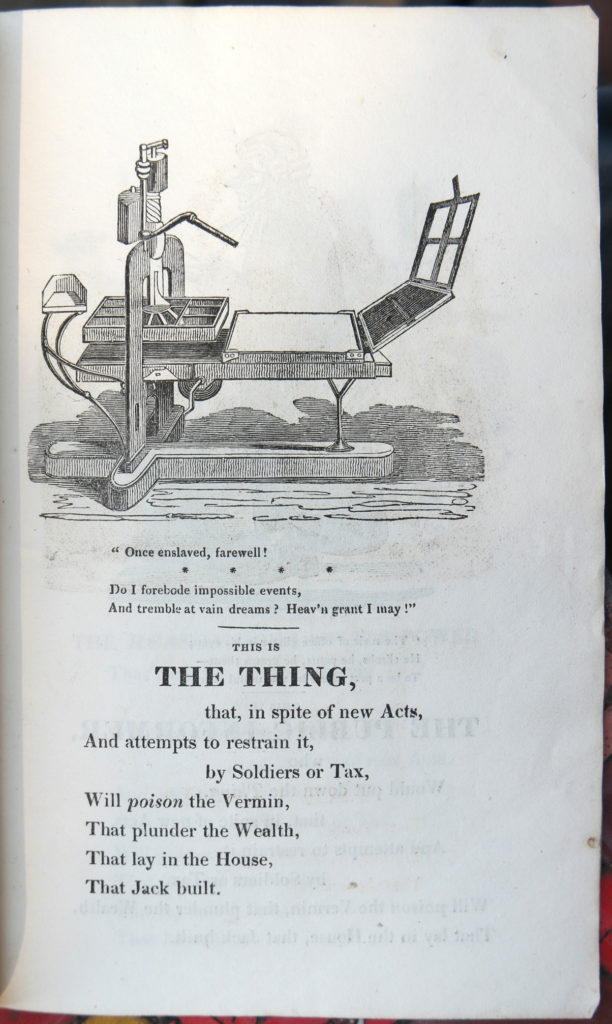

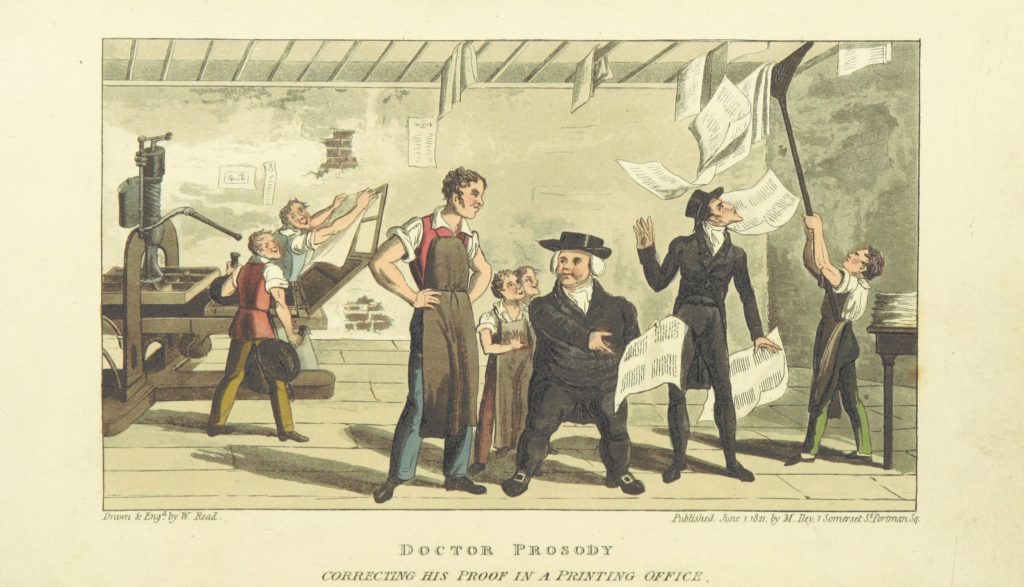

There’s a wonderful contemporary poem by another Briton who ruffled the feathers of the establishment, William Hone, referring to the press as “The Thing,” illustrated with an impressionistic Stanhope by young George Cruikshank, in his pamphlet The Political House that Jack Built, 1819 (51st edition, 1821), one of the earliest representations I’ve found of a Stanhope press. There’s another image, titled “Doctor Prosody correcting his proof in a printing office,” that was engraved by W. Read & published June 1821 by M. Ray in London (this one looks like it was copied from Cruikshank’s).

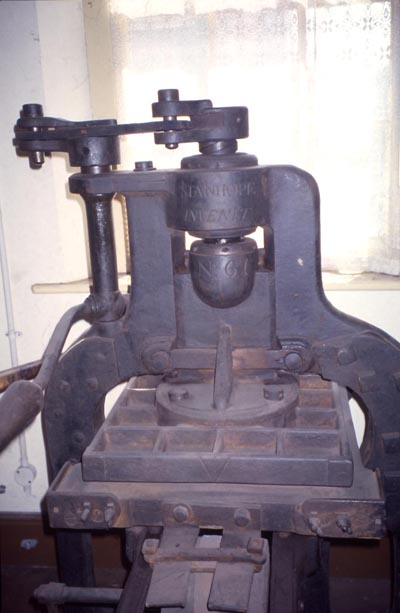

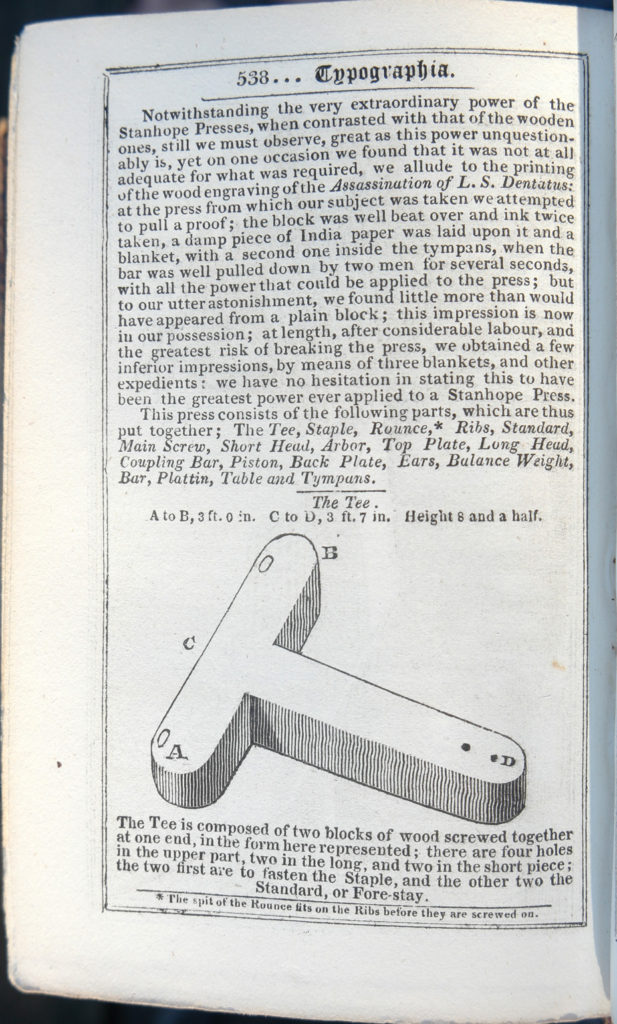

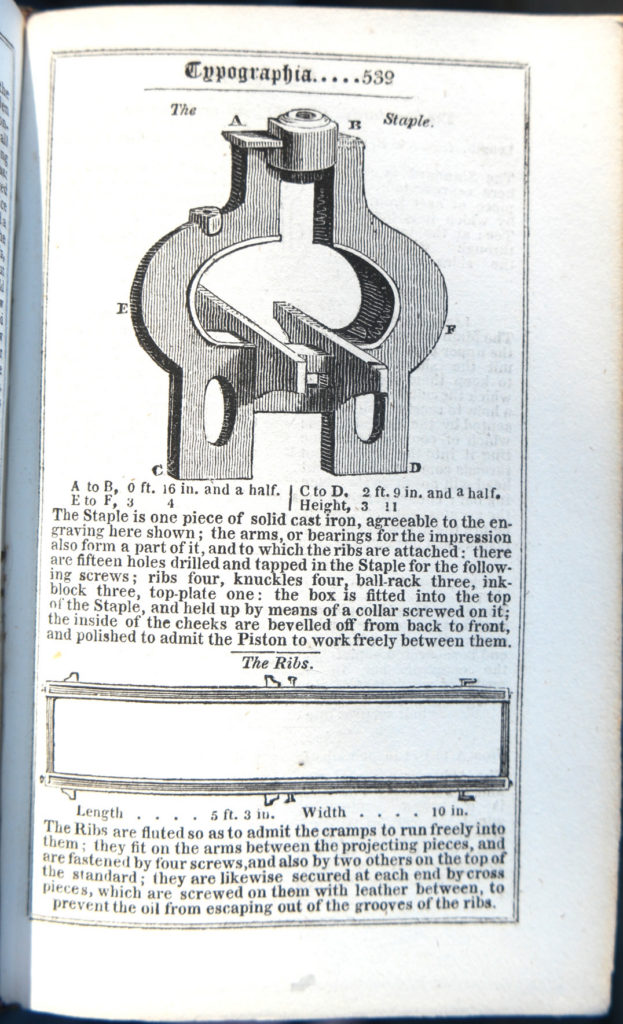

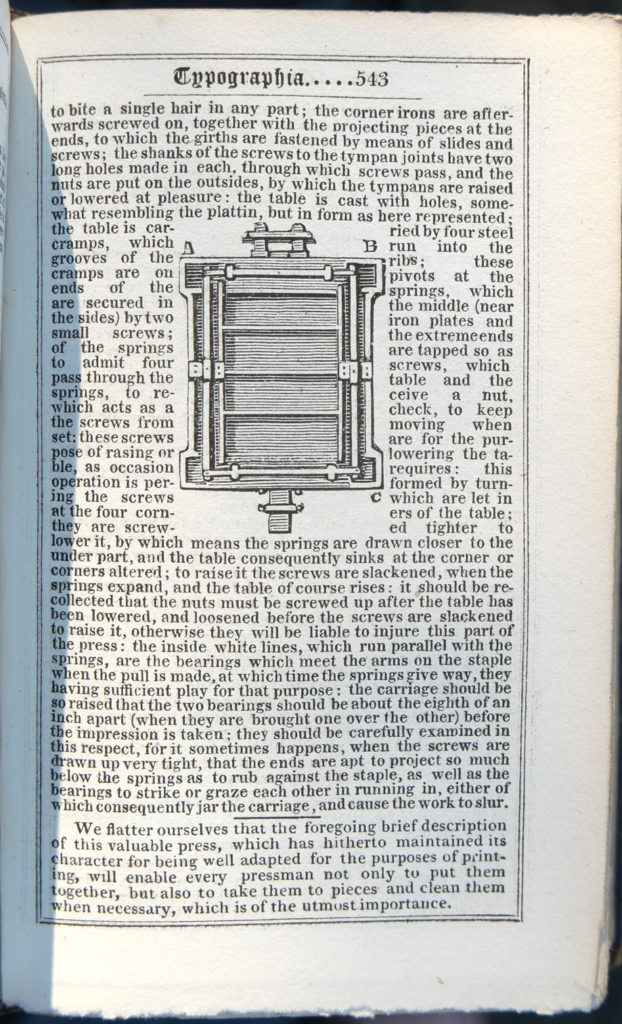

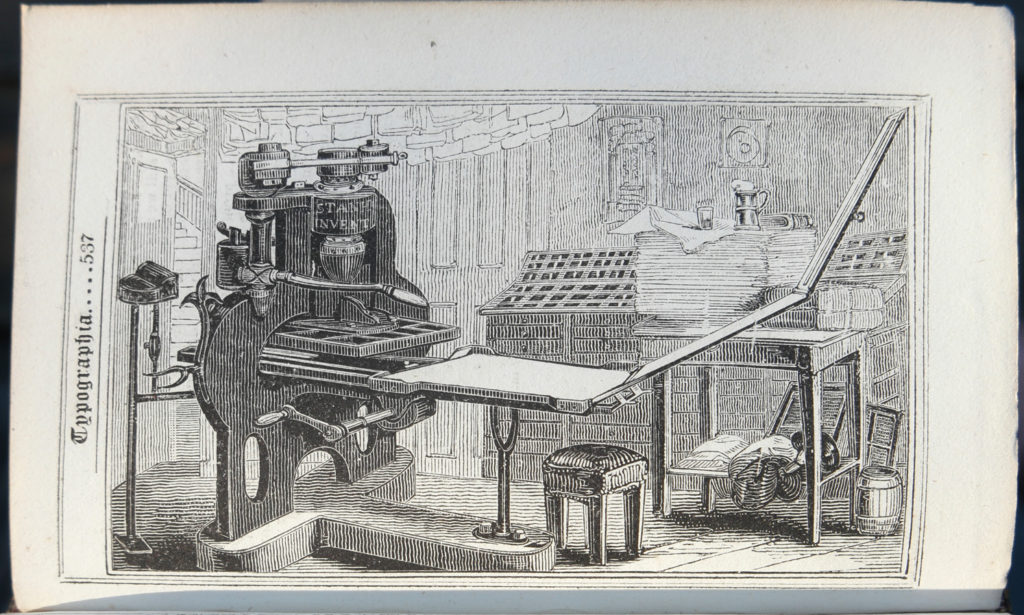

Dr Prosody was an imitation of Dr Syntax whose tours were all the rage. Both of these engravings show a Stanhope of the first construction, and printers still using ink balls, though Earl Stanhope was instrumental in introducing the composition roller. In these sketchy drawings the presses look thin and insubstantial, quite the contrary from their real life appearance. There’s a more accurate rendering in Caleb Stower’s Printer’s Grammar of 1808, and a lovely rendering in John Johnson’s Typographia, 1824 [shown at the bottom of this page]. But seeing them in engravings of varying accuracy made me curious and seeing one in the iron at the Science Museum in London (no longer on display) made me downright covetous. Some printers collect old presses just to enjoy owning them. My goal is to print on it, as it does in fact represent one of the great improvements in printing technology. We searched for nearly 25 years and several came tantalisingly within our grasp, but ultimately were whisked away to spend their days gathering dust in a museum.

In 1984, James Mosley (then Librarian of St Bride’s in London) put us in touch with Bentley Photo Litho in Oldbury, West Midlands, UK. They were selling their 1810 Stanhope (#363) for £5000 pounds (then $6000). We agreed to buy it and sent my brother to their plant to figure out how to take it apart and put in in a crate with wood shavings to get it to California. They had heavily restored it with varnish, epoxy and so on, and were promoting it as a showpiece for display.

Meanwhile, they wrote and said they also had a Columbian for which they wanted £10,000, saying further the presses were a “pair” and should go together. We called Roger Levenson and tried to find someone who wanted the overpriced Columbian. Roger found a Canadian university who showed interest, but in the end Bentley made a deal with Ernie Lindner and the “matched set” went to the International Museum of Graphic Communication in Los Angeles. Lindner was a press salesman whose mandate was to take anything in trade and scrap it, in order to eliminate it from the used equipment market. A clever strategy. But Ernie’s way of eliminating the junk he acquired in trade was to hoard it. He had a miniature table-top Stanhope, La Typote, which belonged to Muir Dawson and for many years sat atop a bookshelf in Dawson’s Bookstore in Los Angeles.

From James Mosley’s appendix to Charles Earl Stanhope and Oxford University Press I discovered there was a Stanhope in Morpeth, Northumberland: a town where I had gone to school (& passed the spot every day for about 6 years as a young boy), so, on a trip to England, I went to see it. It was clear that Mackay, the stationer, wasn’t selling it. It served mainly as a large ashtray for the pressman who was running the cylinder press! It is the second oldest one in existence (#9, from 1804) and had been in Mackay’s family since the 1820s when it was bought at auction in Newcastle. His business was thriving and he had a little grandson who would grow up and inherit it. He mentioned an American who had come by one morning with a bottle of champagne and tried to talk him out of it (Ernie again?); he was amused by the attention.

I spotted another Stanhope (#67) in pieces at the Beamish Open Air Museum in County Durham. It had come from the Middlesborough Gazette. It was another of the earliest construction (with the reinforced bottle-shaped cheeks). On a later trip to England I went to see it again, wondering if I could talk them out of it, but it had been re-assembled and is now in a storeroom there. Justin Howes warned me if I tried to buy any of the early ones he would be sure I couldn’t get an export permit.

Then the ever-diligent James Mosley told us there was one for sale (#50) that had been Hilary Pepler’s at St Dominic’s Press in Ditchling (where Eric Gill had also worked). I wrote a letter of enquiry but got no reply. I assumed it was because I was writing from the USA and they weren’t interested in seeing their press go to some crass American. This press is the one Justin bought & he bequeathed it to the Ditchling Museum. Museums may be good places to preserve old equipment but they don’t use the things and this is a shame when you are talking about a printing press. They were designed to be cheap and efficient ways of reproducing texts and still only involve labour and materials — no more than you would put into a digitally designed book and, best of all, they don’t rely on buggy software or electricity. However, I recently got a letter from the Ditchling museum complaining about my dismissive statement, and telling me they plan to put the press into service and have demonstrations and printing workshops using it.

I heard about this chap who had gone to Cambridge & studied bibliography under Pip Gaskell with James Mosley, Gillian Riley and Nicolas Barker, and he had a Stanhope which he used occasionally to print church services. I think it was in Norfolk. I called him and asked my nephew to drive me there and we paid him a visit: he was an elderly gent with no family, but had promised it to a young friend of his, who didn’t actually want it, but wanted a car instead. He said he would sell it for the price of a new car, but wouldn’t put a cash value on it. (I’m happy with a Honda, but more insecure folks need Hummers.) I spent a day with him and got nowhere. Justin reported he had spent a terrible weekend in the same pursuit. (Or probably being pursued after a few glasses of Chardonnay.)

In 2005 Brooks College, Oxford, decided to sell their machine (#341) as the students were not interested in using it. It wasn’t the nicest-looking one as the wooden base had been replaced clumsily, however I bit the bullet and put a large bid on it. It went for an astronomical sum (£60,000 pounds sterling) to a Japanese museum. This same museum had been advertising in The Printer so I knew they were on the hunt, and I was surprised they had not found the one in Norfolk. It was sold “as is,” and I later heard the collar was cracked and it was going to be a major undertaking to repair it. This news came from Charles Whitehouse of The Iron Press in Switzerland whom I happened to run into at St Bride’s in London while doing some research.

[Printing Museum Tokyo; photo by Ben Jones]

[Printing Museum Tokyo; photo by Ben Jones]

Though they do turn up from time to time, the English Stanhopes are no longer just old proof presses in some dusty corner. Of the 500 made by Walker and Spiers, his successor, there are only 19 recorded (and 5 by makers other than Walker). I figured there were no more non-institutional ones left in England, but then I heard Erik Desmyter had found one in the South Seas! (I have been to Maui but the printing museum there was closed when I visited.) So we turned our attention to France and found one for sale and got some faxes from the seller, but Frances, who lives in France most of the year, went by and the place was closed. She called many times and got no reply. Apparently he was not really selling it, like so many of these collector-dealers.

A web search indicated there was one nearly in my backyard! I visited the owner, Ted Salkin, in Northern California. Another press dealer, Ted has a fantastic collection of printing equipment. He now has two Stanhopes (one French, one possibly Belgian) but I didn’t think he would sell either. In his private museum he has one of every type of iron press, including a tiny field press from the Civil War with a conical roller. The only one he doesn’t have is a Ruggles, fore-runner of the platen press, of which only three are known. One of Ted’s Stanhopes, obviously unique, has iron feet instead of the wooden T-base.

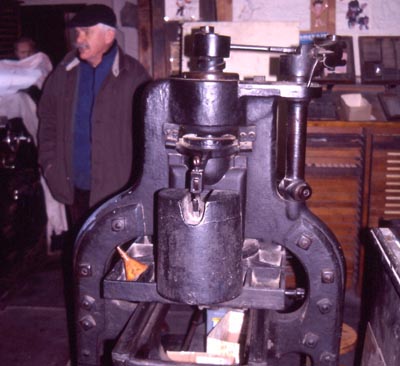

Then one morning I got an e-mail from Eric Holub. He sent me a link to a start-up printing museum in Florida, run by a Heidelberg repairman who, typically, collects old machinery on the side. Eric had spotted a Stanhope that looked like a Matchbox toy in a huge wall of old iron machines. After several e-mails the dealer agreed to sell it. He was disillusioned with his museum. The government had shown interest in one of his presses which predated the model in the Smithsonian, so he decided to sell it to them, but they wanted it as a donation. Plus his ex-wife was suing him for support. So now he was less anxious to build a collection and fortunately for us he didn’t realize how rare the Stanhope is, and offered it to us for a pittance. He assured me it was in working order. I sent him $1000 deposit and flew to Tampa and paid him the balance in cash. As he was counting the money I discovered the ribs were snapped at a crucial juncture right below the bed. It looked as though he had tried to pick it up with a forklift. He acted innocent. I didn’t know you actually wanted to use it, was his comment. (He had photographed it from every angle but cleverly disguised the broken ribs in his photos.) However I could see that otherwise it was nearly complete & it was still a bargain. There was no point in asking for a refund or a discount: he was out the door, leaving me with his staff.

It was nerve-wracking getting it here. I had to pay his brother an extra $200 for a new skid and to have him load it on the Roadway Express truck. Roadway’s shipping charge changed from week to week, it started out at $1800 and then went up for the gasoline surcharge. Then I told them it was used equipment — basically scrap iron — and they came down to $800. When I called their tracking hot line it seemed to be stuck in Dallas, waiting for someone to go to Oakland. Then they called back to say they were revising the bill. I thought they were going to stick it to me, but they lowered it to $400. But then I needed a rigger to get it off the truck and into my basement. Needless to say it cost twice as much to get it the last fifty feet as it did to get it the 3000+ miles from Tampa.

Next I had to restore it, & I began to dig through the ancient grease which, in some places, seemed to be holding it together. The press was originally sold by Lorilleux, the Parisian ink manufacturer, but almost certainly made for them by someone else. We are still researching its history. Eric Desmyter warned me not to overdo it and keep as much of the original paint intact as possible, so I polished the brass and retouched the cast iron with stove polish. The wooden T-shaped base was rotting in places, particularly at the joint. I chipped at it with a chisel and it crumbled. So I bought a gallon of marine epoxy and poured it over the oak base. It changes the chemical structure of the wood but is the only sure way to hold it together without having to replace the base. I commissioned a wood-turner I found on-line to make a new handle for me out of cherrywood and sent him a diagram based on the tapered flange of the handle, and the swelled shape I saw in old engravings. I also needed half of the frisket replaced, and went to Mork welding, who did a great job, but seeing it was an antique hit me with a fine price.

Through another Bay Area press collector, Fred Voltmer, I got in touch with Peter Johnson, a skilled welder who could stick the ribs back together for me. Peter collects & restores old motorbikes with the same passion we press nuts have for our old machines, and he loves working with challenging projects, but this one really daunted him. It’s not the expensive flux, he told me, it’s the fact that if the temperature is wrong the iron will simply melt. He had the parts for a year working up the courage to do it, and I began to despair of his getting back to me, so I investigated getting new ribs cast which turned out to be incredibly expensive. For a year I looked at the press. Periodically I would go at it and clean out some grime, using ink knives, tweezers, my make-up rule, a toothbrush, various solvents and degreasers. I got to know every corner of it.

In the end Peter came through superbly. He not only welded the ribs back together, but re-tapped and reinforced the bolt holes. One of the welded ribs has warped slightly while cooling (packed in ashes so it would cool slowly) and Peter had to torque it carefully back to be true. We discovered that although the press had been most likely built in France it was constructed pretty much in English inches. The bolts were 3/4 inch, some others were 7/8th, but not quite. Perhaps many of these parts were custom made, so they didn’t go to the hardware store and buy four 3/4″ bolts: they made tools to make them. France had not adopted the metric system until Napoleonic times (proposed 1791, established 1799, made law in 1816, rescinded 1825, reinstated 1837), but it was intriguing that the makers had followed the Earl’s model so accurately. I doubt that you could build one from the drawings in Hansard, Timperley, etc, but would need a model to copy.

I wondered how the nineteenth-century printer had been able to assemble and disassemble these machines. The weight of the bed on the broken ribs had bent the footstay and Peter said he would straighten it with a hammer, but two knocks and the bolt broke. It all seemed so friable and I was sure the whole thing was going to crack and be a fancy souvenir ashtray after all. The tympan had been covered in felt. It had been designed this way and the sides had wooden inlays for nails to stretch the felt. I pulled out the tiny upholstery nails with pliers and went to the fabric store with a piece of the old felt. You can’t get real felt like that, the saleslady told me, but if you boil this felt & dry it in a hot dryer it will become denser. I did that, then I was ready to try an impression but it looked horrible. Forget the soft packing, James Mosley e-mailed me. It was finally time to look at the manual. Gabriel Rummonds suggests Permalin but I couldn’t locate any, but Mylar seemed to be a good solution for a hard tympan cover. One of my former students, Les Ferris, who now teaches a class with the Berkeley Albion, suggested instead of covering the frisket with tympan paper and cutting windows I could use elastic braid & keep it off the forme with foam weather-stripping. It’s a great expedient and looks very high-tech, I am sure the third Earl would have approved.

I set a block of large Caslon to try out the press: “The Great Panjandrum” by Samuel Foote, a wonderful nonsense poem from the 18th century. When I couldn’t get an image I wondered how much packing I would need, then I saw another piece of transparent technology: There’s a thumbscrew that adjusts the depth of pull, and by twisting it you can adjust the amount of impression by infinitesimal amounts, as on my adjustable-bed Vandercook. With a little practice my brayer technique is starting to come back.

Fred came by with another press nut from Southern California who teaches a class on the hand-press at his school. The two of them got on their knees, not to worship at the vision, but to check out the underside.

You’re missing bolts, they said. I got down too. There are two big suspension springs running the length of the bed, also adjustable to raise or lower the corners of the bed. Two more half-inch bolts from the hardware store fixed that. But the side plates to hold the chase on the bed were gone. I measured the screw holes, did drawings on graph paper, and commissioned a sculptor friend who has a high-tech shop with fancy metalworking equipment. “You need it this year?” he asked. I thought he was kidding. A year later I bugged him and he sent me the plates and a bill. They didn’t work: he’d ignored my drawings and “standardized” them. I called D. M. (a friend of Peter Johnson, and another “old tool” enthusiast). He made the plates accurately in 24 hours. Now I needed flat-headed brass screws that would fit flush so as not to impede the movement of the bed. No luck. How about hex-headed Allen screws? Well, okay, perhaps the Earl would dig that little modern touch also.

Ships have names, so why not printing presses? I have dubbed this Stanhope “le Citoyen.”

The pressman, having finished his run, has left his beer perched precariously

while running upstairs to answer the door, or check his e-mail…

[updated August 2012]